We Are Making the World Reliable

$20MM+

Invested in R&D and Ventures, focused on industrial reliability and data science

2MM+

Assets implemented and analyzed for reliability and integrity programs

500+

Employees dedicated to improving reliability, with 50% embedded in customer sites

20+

Reliability software packages implemented to enable data-driven decisions

What We Do

Reliability as a Solution

Our fixed price service plus software solution focused on delivering to a quantified result.

Data-Driven Reliability

Data-Driven Reliability is the lens we use to view the impact of data across an organization.

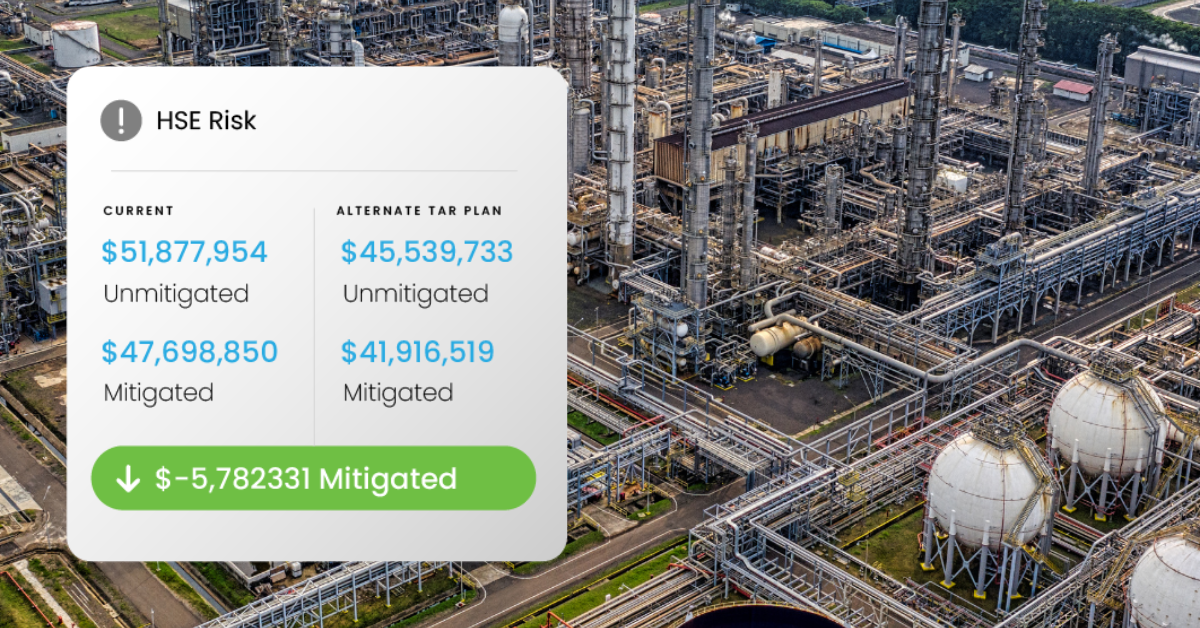

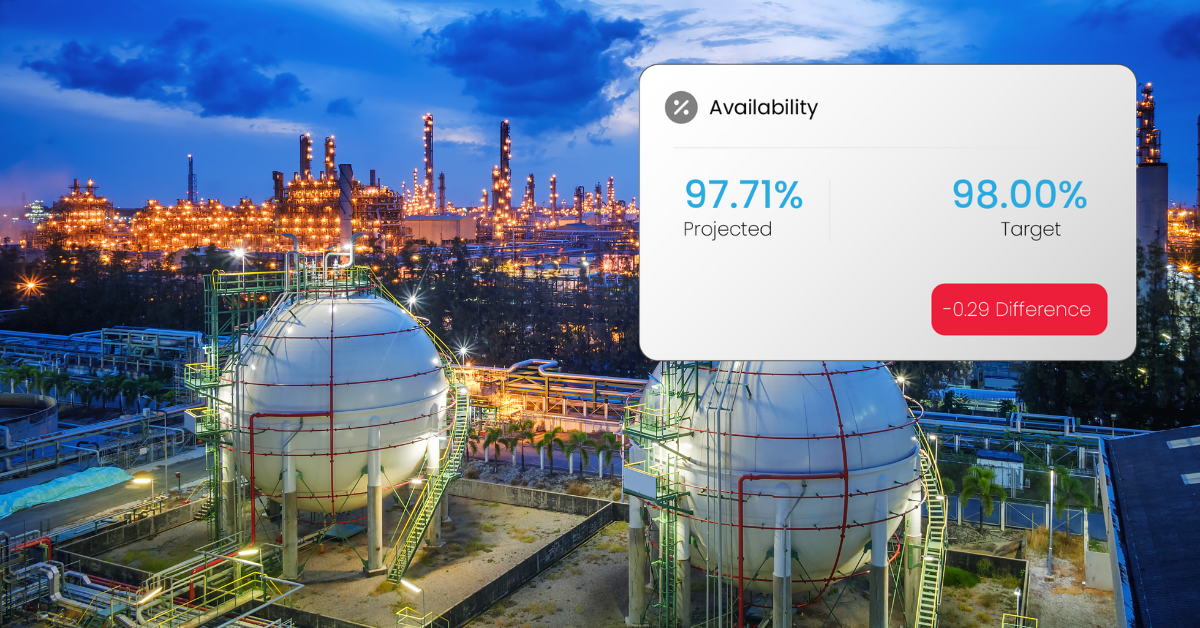

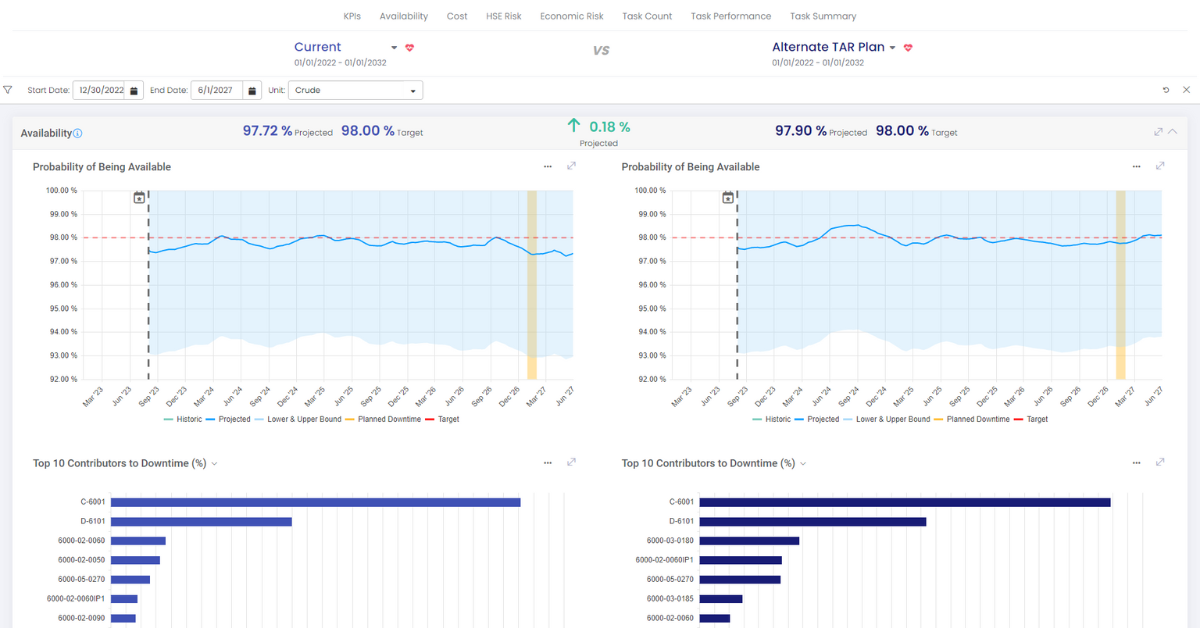

Newton™

The suite answering “What happens if this compressor blows?” or “Can I push this inspection?”

Trusted Reliability Partner in Over 200 Facilities

Our team is built to serve our customers in the best way possible, focused on driving excellence, making an impact, and prioritizing growth.